By: Bryan Ricardo Marini Quintana

Moreover, Meditations harkens back to the philosophy of the Socratics with Epictetus’ teachings on the principles of moral virtue. Here, the Emperor contemplated how to discover his spiritual voice and speak with his “dæmon” to live in agreement with the universal nature. This brought Marcus Aurelius in contact with divine counsel, as the “logos” advised him to pursue what was meaningful and avoid distractions. Among these troubles, he warned himself against chasing after worldly desires and bursting out in fits of anger. Marcus Aurelius voiced this struggle to care for one’s soul by controlling his impulses when he conveyed: “Repentance is a kind of self-reproof for having neglected something useful; but that which is good must be something useful, and the perfect good man should look after it. But no such man would ever repent of having refused any sensual pleasure. Pleasure then is neither good nor useful.” (Meditations 75)

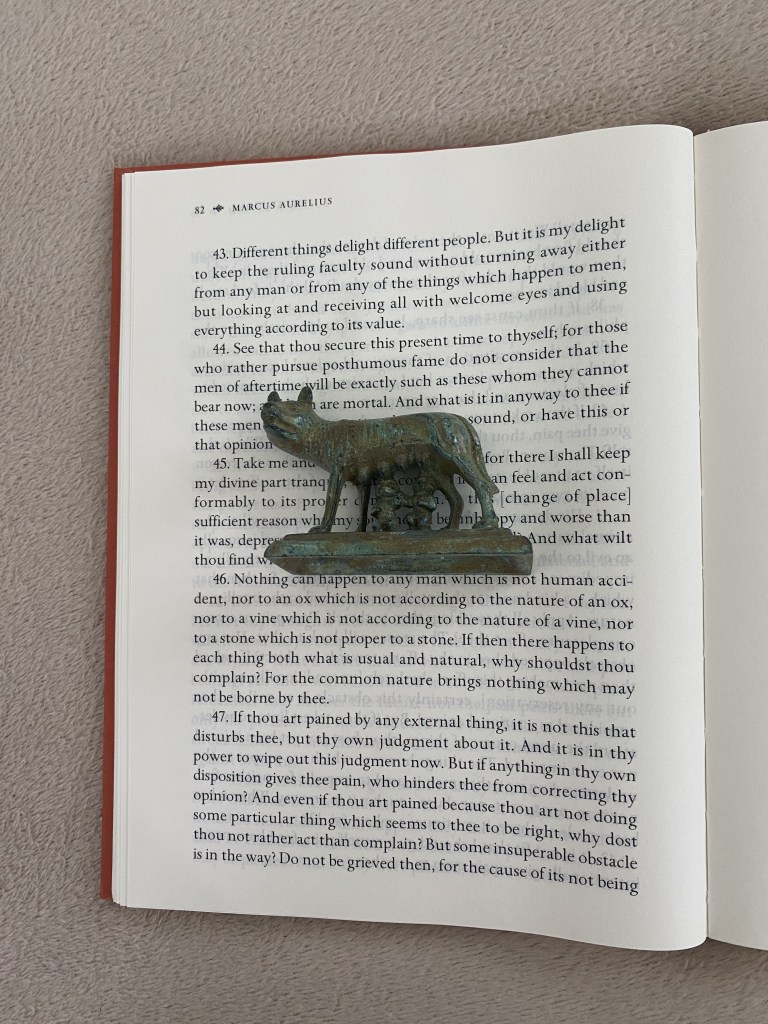

Then, the Emperor reasoned that he must balance his spirit and the universal law governing outer events, including the unpredictable nature of confronting pain. Since he had no influence over his surroundings, Marcus Aurelius pondered how he could endure an unfavorable outcome and accept the experience with a calm posture. To resolve this dilemma, he argued that the harmful deeds of others didn’t impact his nature; instead, the Emperor’s response to this injury defined his character. Marcus Aurelius displayed his resolve to stomach hardship when he articulated: “For he who yields to pain and he who yields to anger, both are wounded and both submit.” (Meditations 118) Often, the Emperor grasped that his mind’s outlook on a problem was potent enough to alleviate or increase his wound’s anguish. Only by learning to control how he perceived a harmful occurrence could he gain inner peace with his “dæmon” and “logos” instead of falling into distress. Accordingly, Marcus Aurelius sought a balance with the universal nature, understanding he held no power over his environment but only how he responded by reflecting: “Wipe out thy imagination by often saying to thyself: now it is in my power to let no badness be in this soul, nor desire, nor any perturbation at all; but looking at all things I see what is their nature, and I use each according to its value. Remember this power which thou hast from nature.” (Meditations 79)

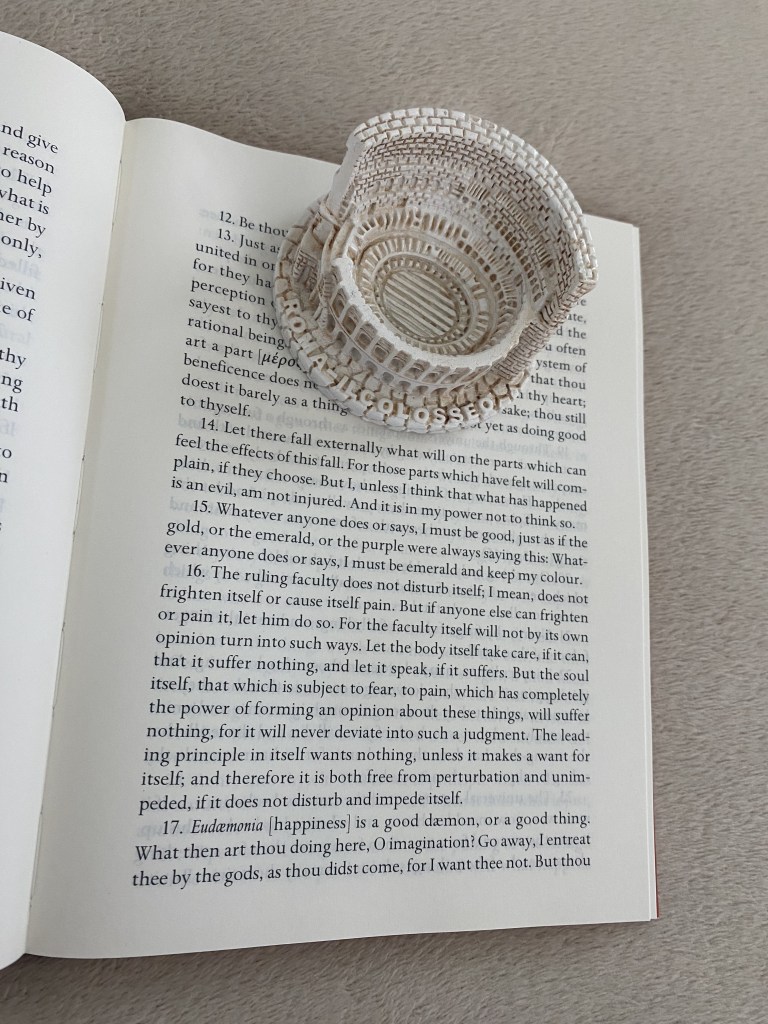

Afterward, the Emperor discussed that a pivotal lesson of Stoicism is that happiness becomes the responsibility of every individual, with the quality of his thoughts shaping a man’s attitude. Consequently, his surroundings can deal a good or bad hand regardless of one’s character. However, Marcus Aurelius didn’t hold himself answerable for the world’s nature but was only accountable for his reaction when facing tragedy by contemplating: “If thou art pained by any external thing, it is not this that disturbs thee, but thy own judgment about it. And it is in thy power to wipe out this judgment now.” (Meditations 82) Therefore, the Emperor understood that he could revoke the notion of whatever disturbed his harmony, exercising power over his mind’s opinion about that which troubled him.

Overall, Meditations records Marcus Aurelius’ personal reflections on how to lead a virtuous life in accordance with the teachings of Stoic Philosophy. Throughout his reign, he relished a life of luxuries fit for a Roman Emperor. He was free to abuse his authority with prideful ambitions that would’ve seen him indulge in every vice, from fleeting pleasure to spewing anger. Nevertheless, he chose to rule Rome’s powerful economic and military force under the beliefs of Stoicism. In his daily life, Marcus Aurelius practiced humility, patience, and gratitude when addressing the challenging predicaments of upholding his character or the numerous crises faced by the Roman Empire. Above all, the Emperor consulted his “dæmon” or “logos” for spiritual guidance and divine wisdom to contemplate the principles of universal change while leading a life of moral virtue. Hence, Meditations serves as the archetypal work of Stoic Philosophy that preserves Marcus Aurelius’ implicit teachings on how to practice wisdom, justice, fortitude, and moderation to master the self, as the Roman Emperor’s pursuit to live righteously in accordance with nature while building a relationship with his innermost soul immortalized him for generations of readers as the Philosopher-King from the Greco-Roman World.