By: Bryan Ricardo Marini Quintana

By: Bryan Ricardo Marini Quintana

Let’s travel across the creeks of the Milky Way

As you’re stashed between my arms

Filling the dull tones of our frames

With droplets of paint that gleam our spirits away

…

We depart a shadow cast by the mantle of space

Arriving upon a seashore teeming with grainy rye

Where we lay barefoot amidst mounds of fruits

Sinking our toes in the warmth of white shores

…

The silver drapes of the cosmos roll back

Thrusting us into luminescent mists

Where we sail a sapphire breeze aboard our vessel

Traversing the depths of a void brushed by blazing pearls

…

Until we arrive at the brink of realms

Docking after our voyage on rich riverbanks

Where we find respite in evergreen pastures

Brimming with waves of never-ending wheatgrass fields

…

These are flourishing with peach and lime tint palettes

As the golden dandelion wanes and the snowy rose waxes

With the flowering of our cherry blossom and marigold sky

That upon twilight, mature into our delphinium and lilac melody

…

We arrive at an unageing woodland that sprouts with mellow plums

Where you bite a berry as the syrup drips over your lips

Upon tasting the fruit, your cheeks blister with a rose fluorescence

Then you offer me a taste as I lunge for your lips to savor the juice

…

In our kiss, we transcend old woes to jubilate with youthful bliss

As we mix our nectar while resting on a bronze bark of golden leaves

Gazing at the glaring haze that gallops above us in the firmaments

Where you invite me to sway in a dance that weaves our spirits’ strings away

By: Bryan Ricardo Marini Quintana

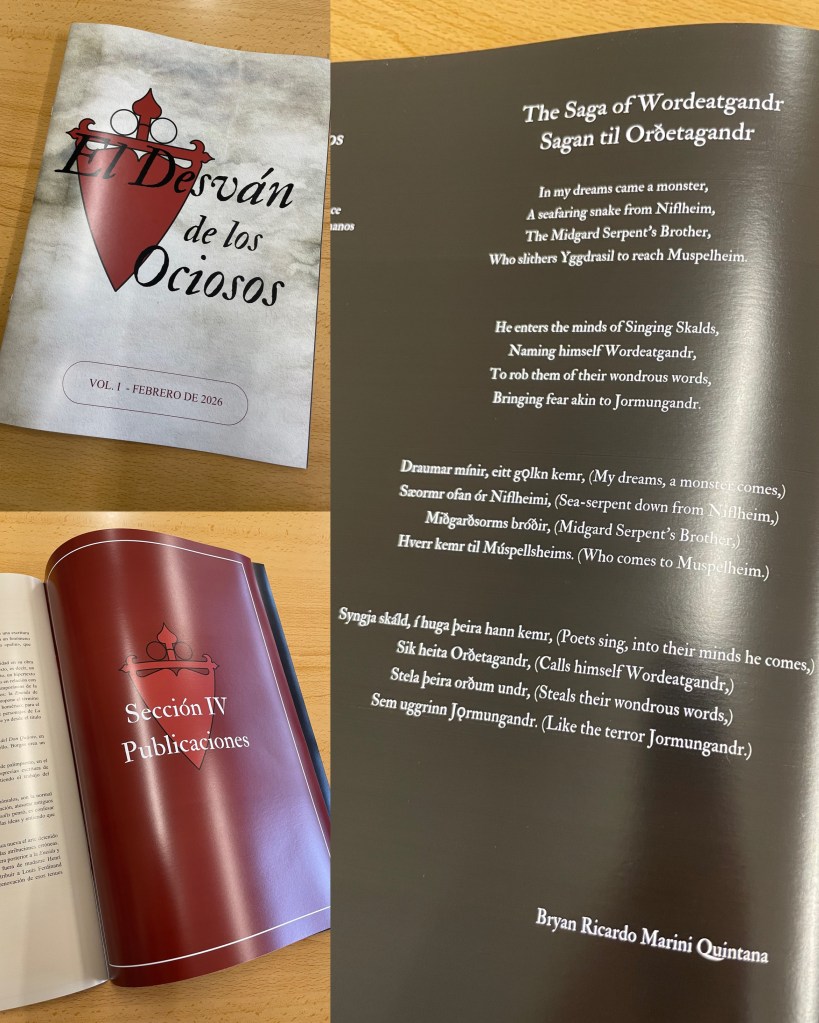

Today, I can finally share my small collaboration through a poem with the New Student Lead Philology Magazine (@eldesvandelosociosos) from the University of Santiago de Compostela!

If you’re on campus, be on the lookout for their first issue!

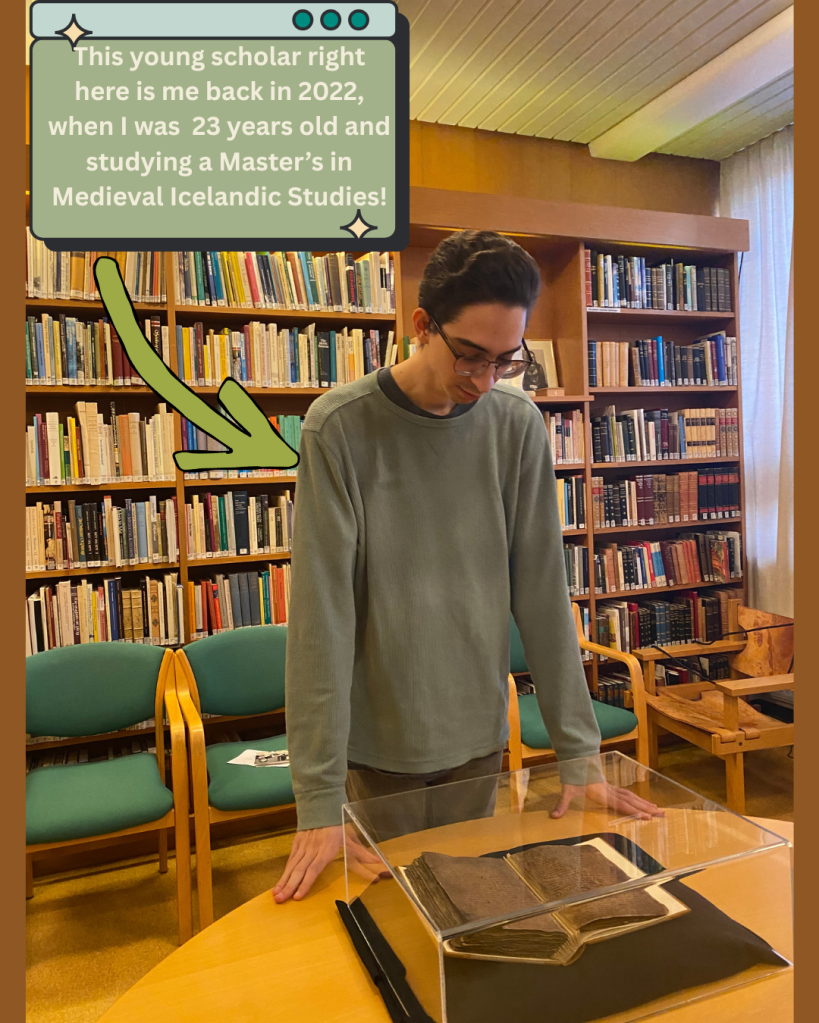

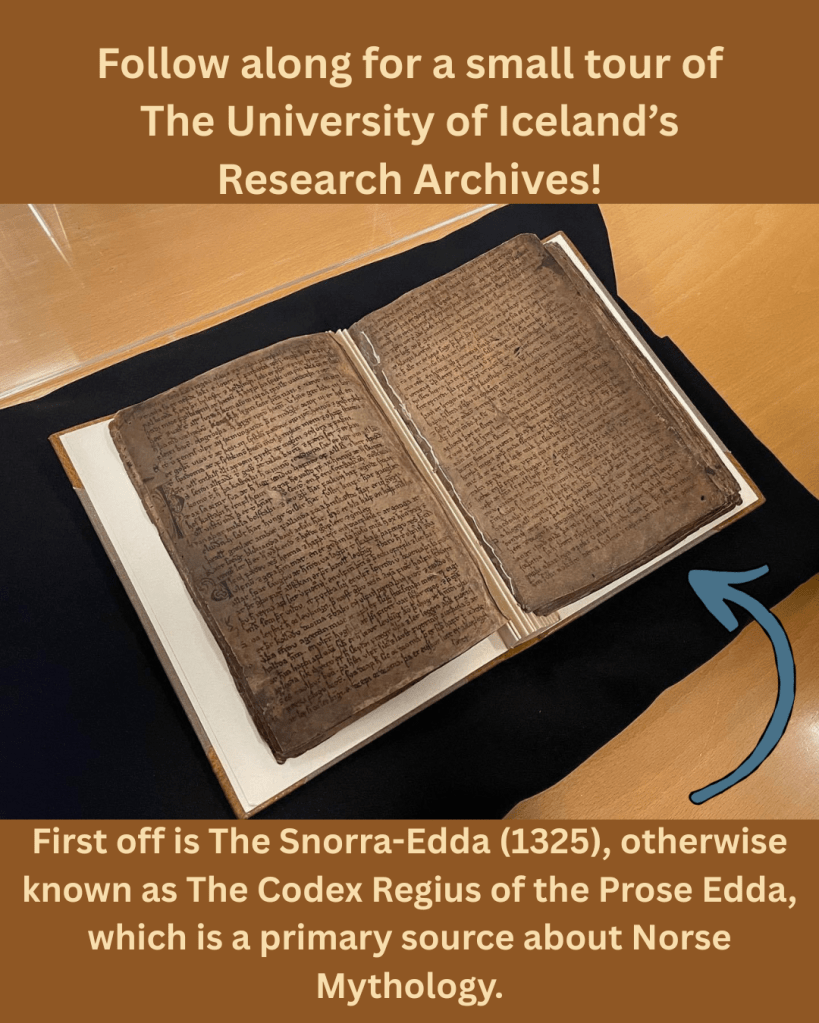

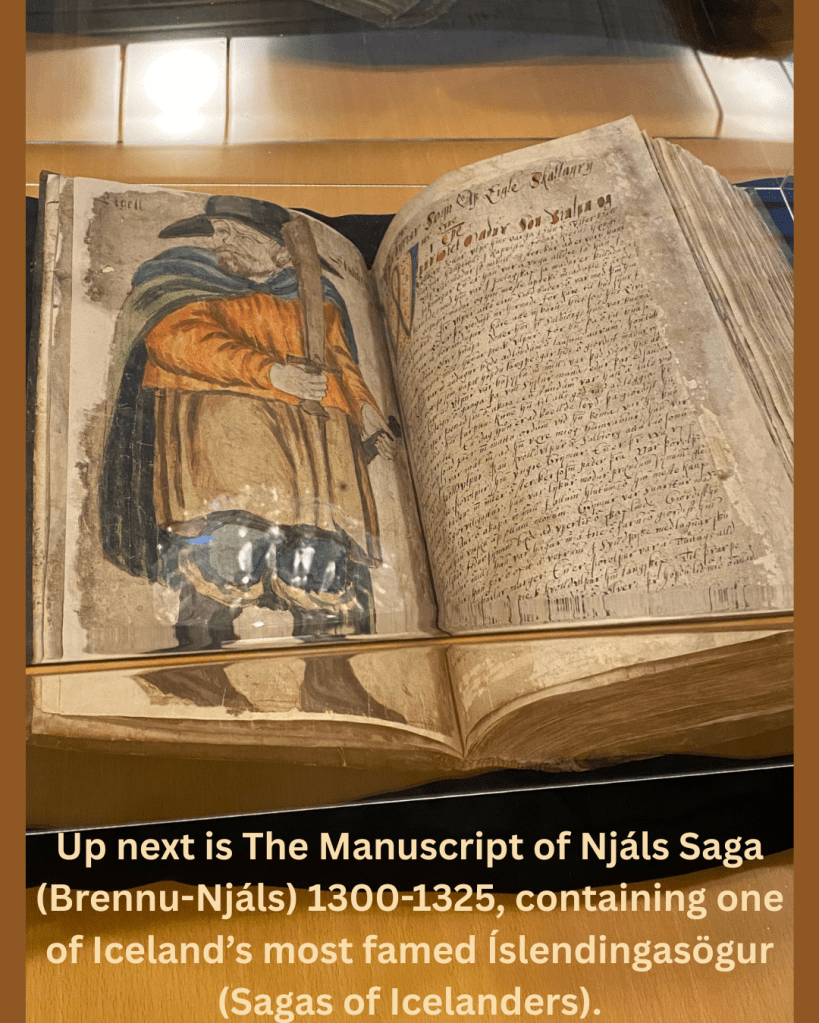

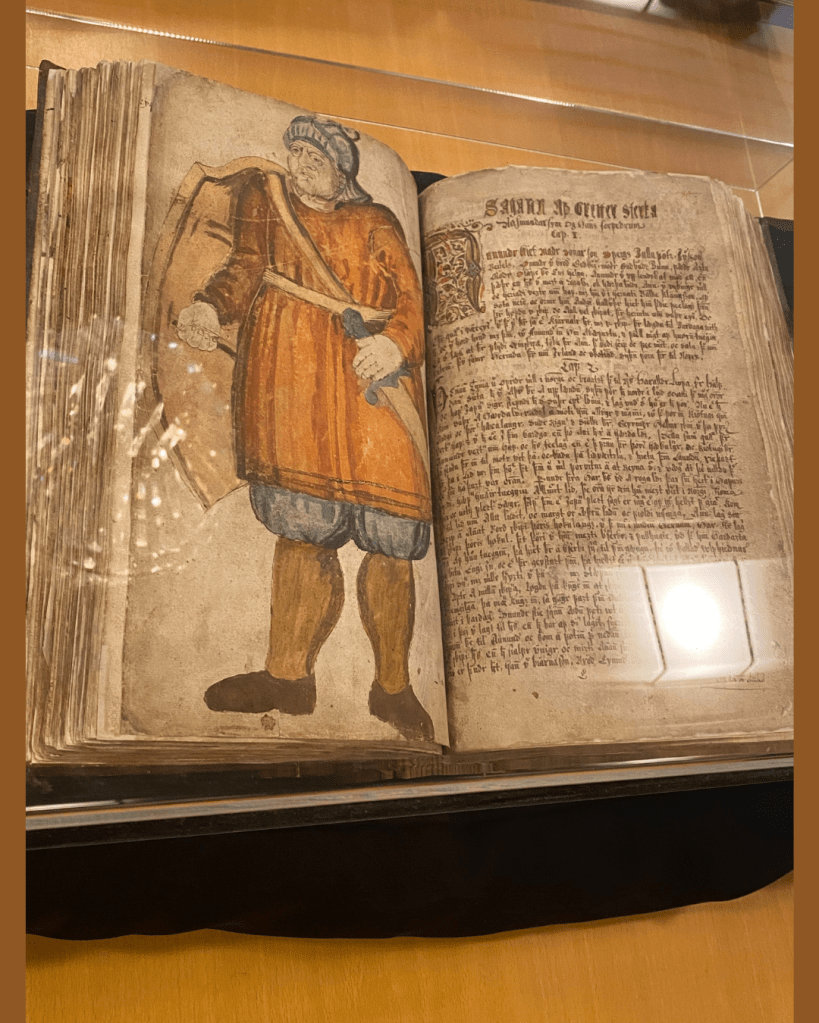

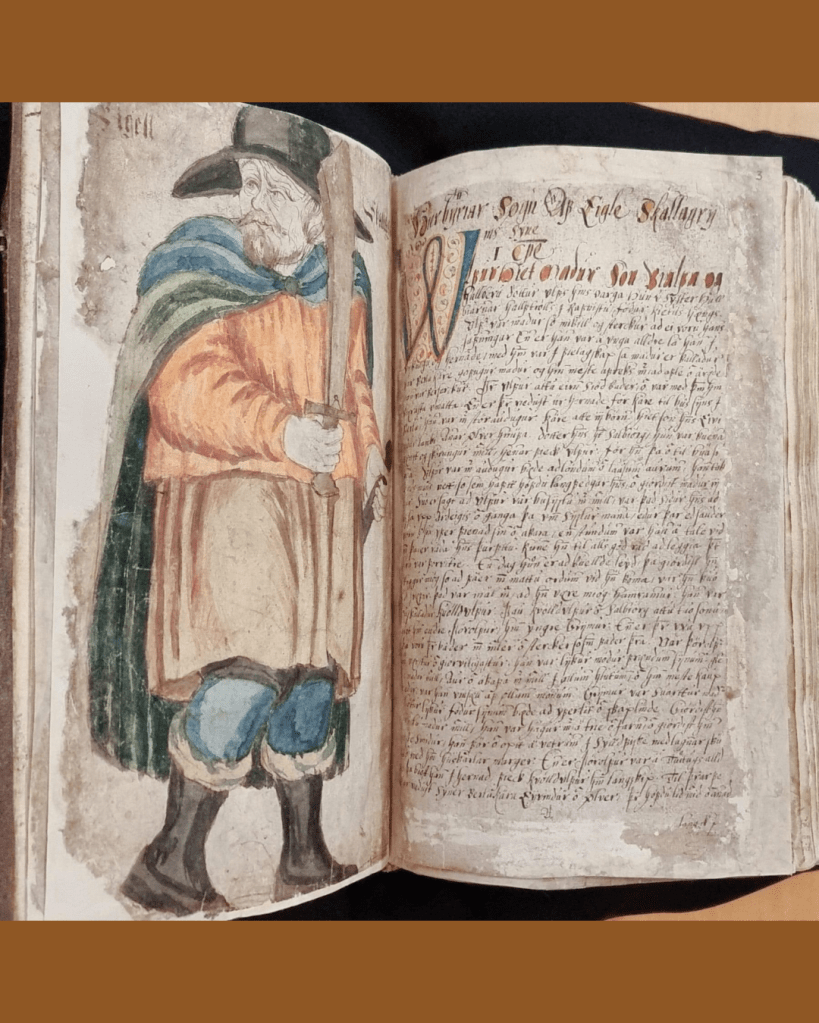

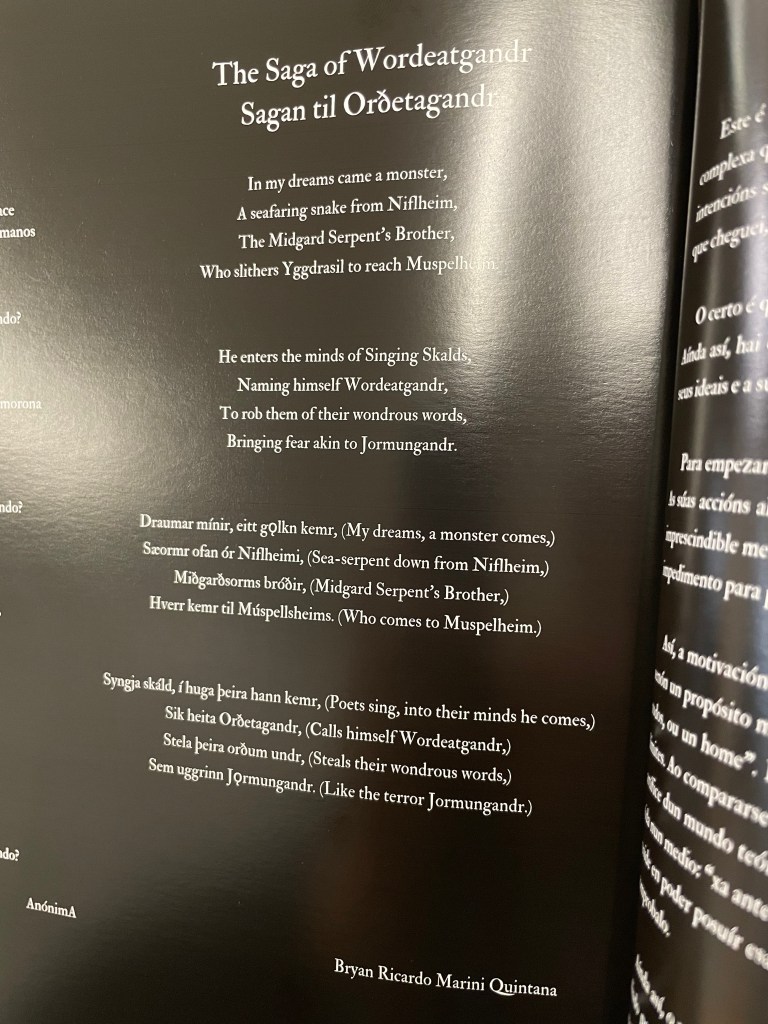

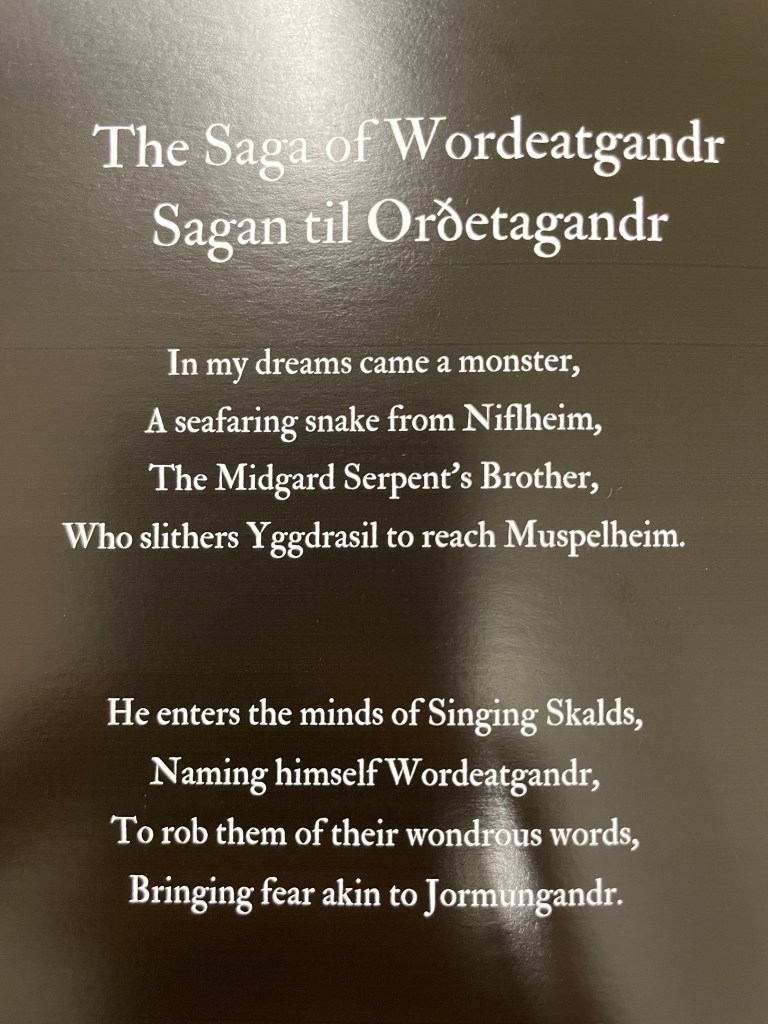

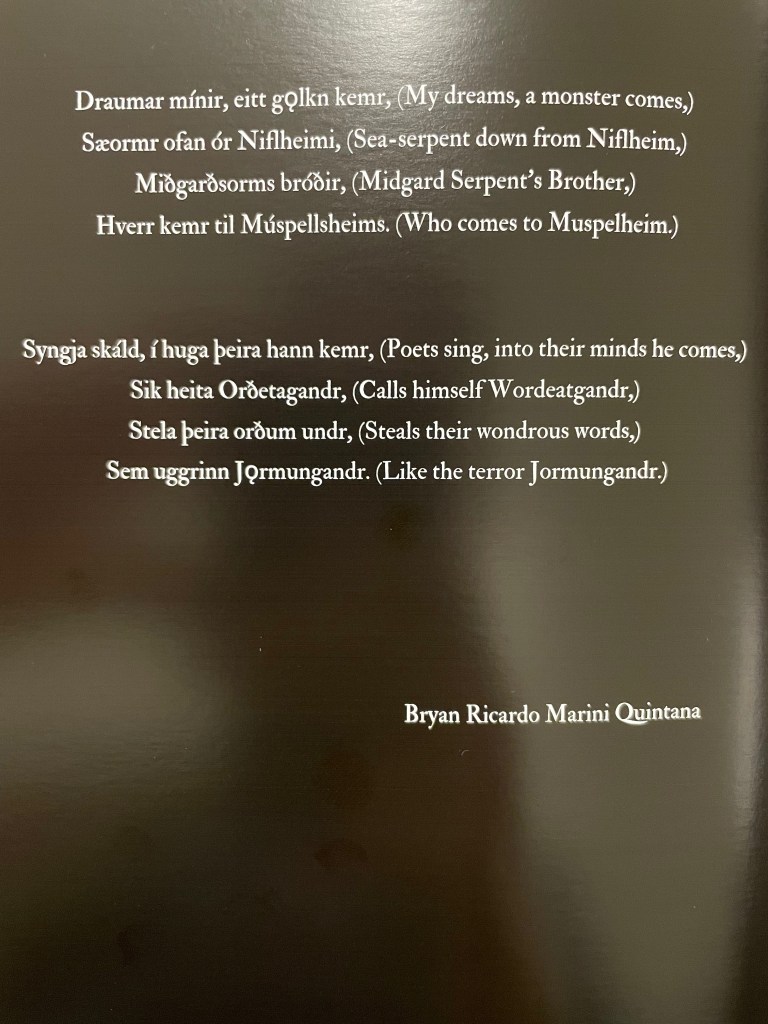

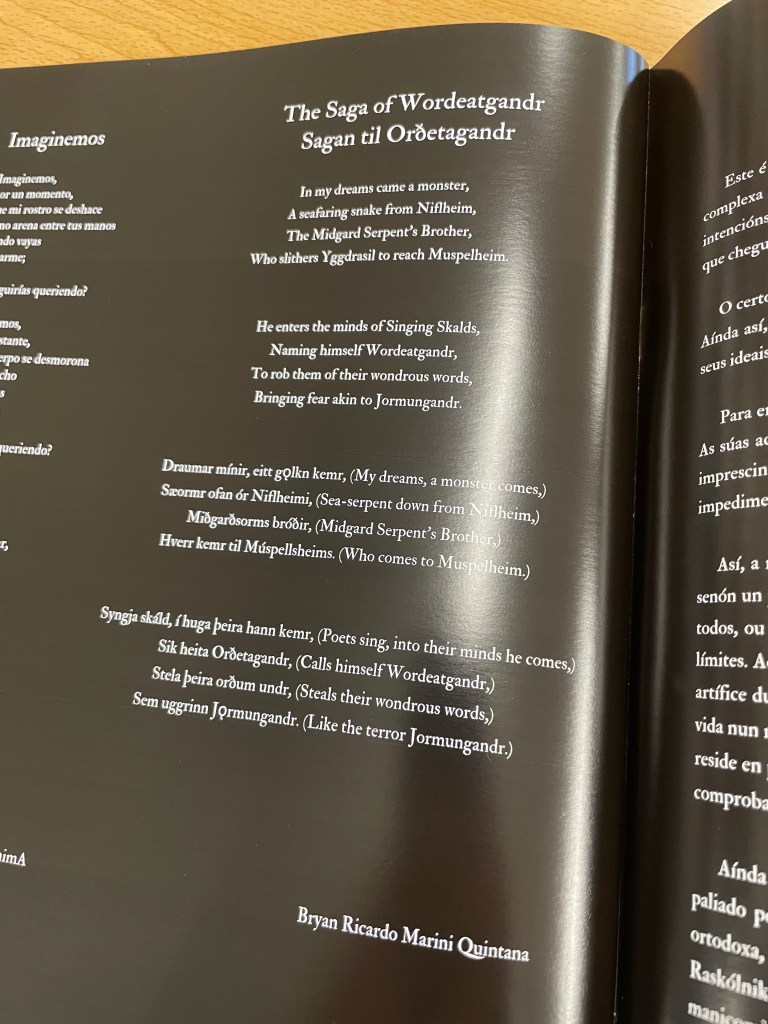

The Saga Of Orðetagandr (Dual-Language Version in English and Old Icelandic)

If you’ve ever suffered from writer’s block or suddenly lost inspiration while composing your story, then perhaps Wordeatgandr slithered into your dreams and devoured your ideas!

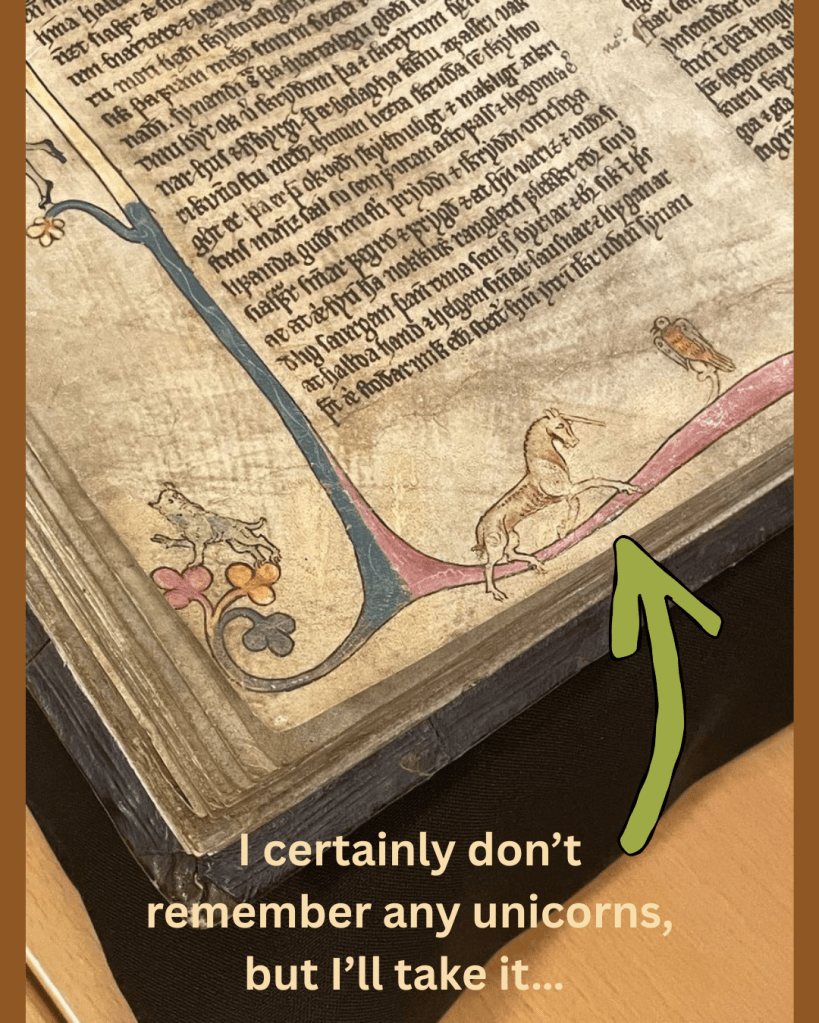

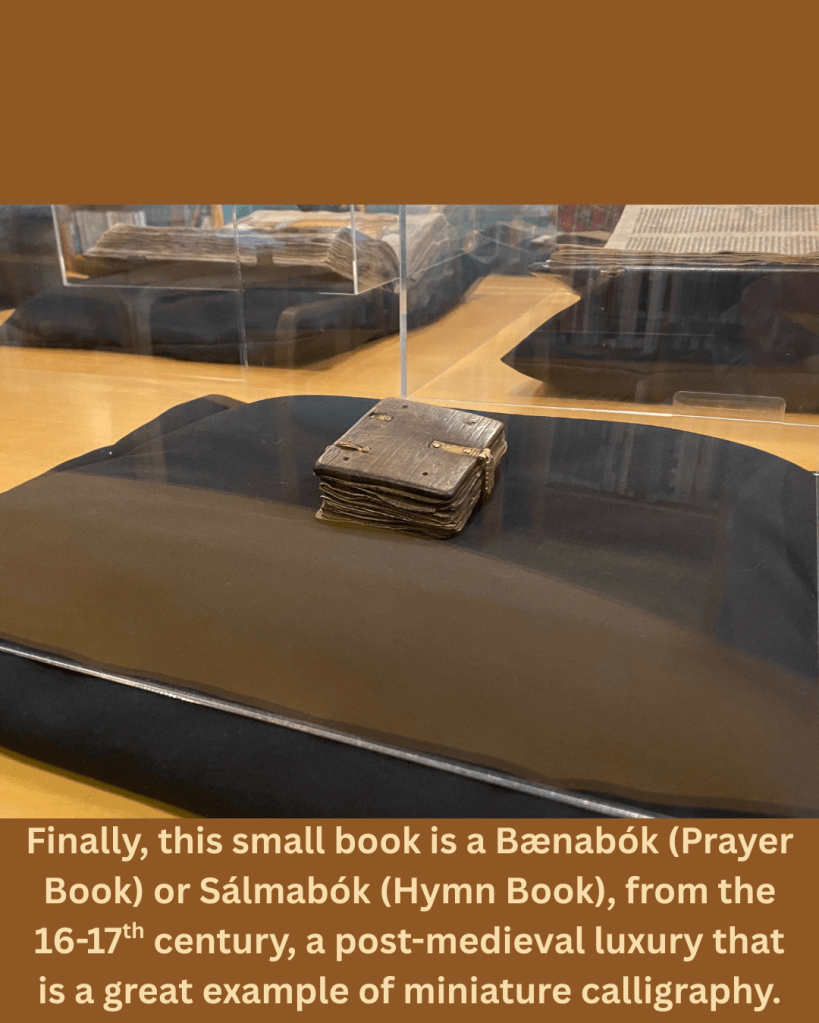

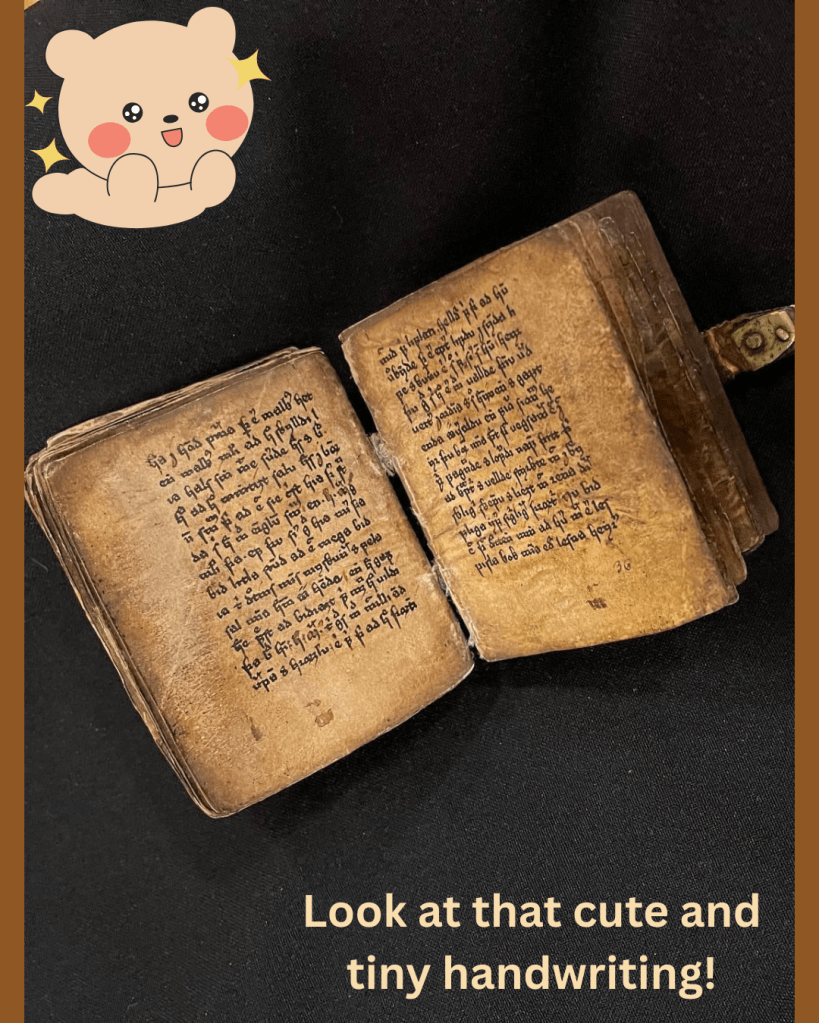

Original Manuscript: (Margrétar Saga, AM 431 12mo, 1540-1560)

By: Bryan Ricardo Marini Quintana

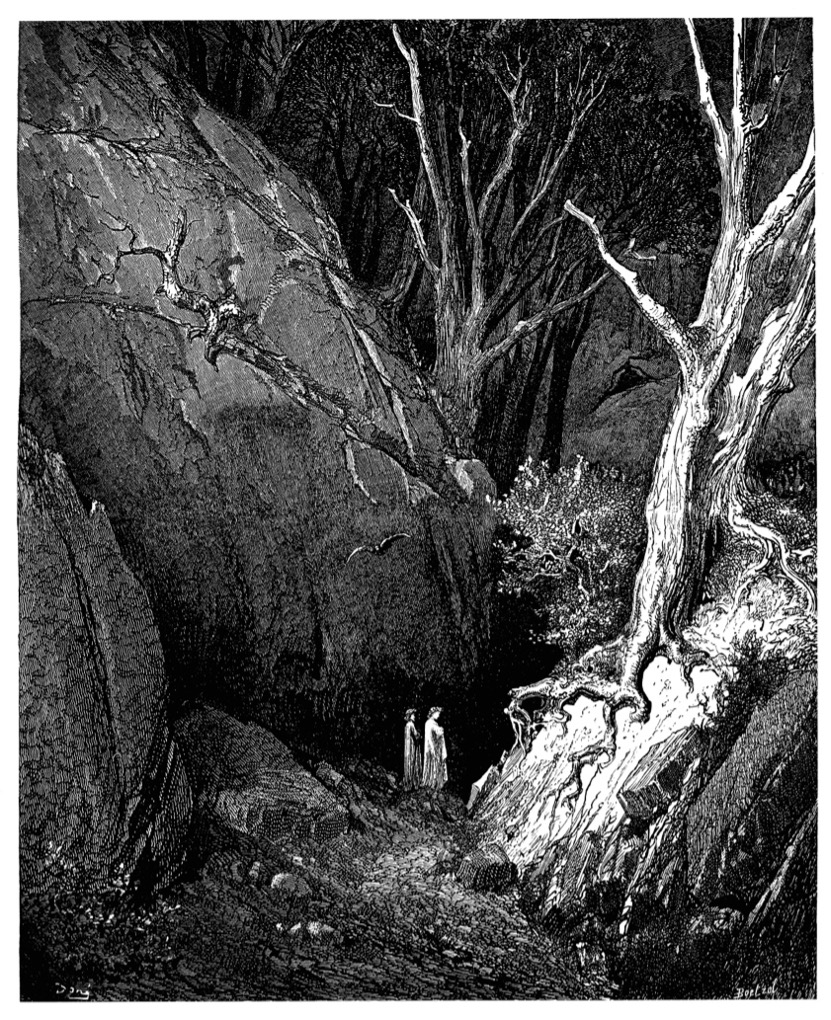

Before Prometheus seized Zeus’ furtive fire to awaken mankind from their slumbering shade, amidst the fabled lands of Hellas and Anatolia arose the mystifying isle of Menodora. Near the maiden’s waters wandered the magisterial vessel of Adamantios, ramming across her white shores in the Aegean Sea. Here dwelled a nymph who held dominion over her woodland realm, enticing a mariner with the mellow aroma of her plums to bind him under a spell. Whilst Adamantios delved ever deeper into the boughs of Menodora, she stretched her branches to and fro, wrapping him beneath her limbs. She then beheld the stout craft of his ship as he glimpsed the bewildering beauty of her magical domain. Thereupon, a spirit became smitten by the form when Menodora slept with Adamantios and conceived Diodorus.

After the moon’s fading and the sun’s rising, the father departed when he was mustered to resume his post. Without hesitation, he chose to abandon his beloved and child, sailing away with a promise to return when his task had been fulfilled. Alone, the mother sprang her seed, nurturing him within her woodland realm. She entwined her branches to cloud him with the gloom of Nyx and the paleness of Selene, bloating Helios’ chariot from fetching the light. Diodorus became shunned from the eternal flame that eclipsed every year, casting a shadow over the rotation of Adamantios’ sundial. Amidst the mystical isle of Menodora, ensnaring vines stretched to the east and west, where her son was confined to the borders of her magical domain under duress by the zealous nature of his mother.

Persistently, Diodorus wailed to be quelled by the breast of Menodora, latching onto her bosom to hide from mankind in seclusion. Amidst bountiful trees, the child was fenced from the seas, towered from the heavens, and prohibited from leaving his mother’s sight. Whilst he grew steadfast in stature, Menodora was reminded of her beloved and became haunted by the recollection of his departure. In his father’s absence, Diodorus lacked form and was cast from his mother’s spirit. She leashed him with slithering vines and forced him to remain at her side, fearful he’d forsake her as Adamantios had. Every day, she gathered the harvest and gifted the labor to him, robbing her child of freely snatching nourishment on his own. Everything Diodorus demanded, Menodora provided by merely mumbling and pointing at what he desired. Infancy bloomed into childhood and matured into adolescence, with the feeble boy now grown into a stout man who had been shielded from all he feared, incapable of uttering the tongue of mankind and picking himself up to tread in their footsteps. In time, the son became maimed whilst his nurturer spoiled him when she ceaselessly recited: “Come mine dear Diodorus and listen to thy mother, thou shall never be compelled to stretch thy feet or declare with thy tongue, for mine woodland realm will deliver thou with every fruit and need, as thy requests shall be satisfied with great haste and heed.”

Thence, Adamantios returned from his perilous journey to her ragged shores, longing to amend for his absence. After forsaking his duty, he sought the embrace of Menodora, haunted by a guilty conscience. However, when the father delved into her woodland realm, he became horrified by the sight of his son still clasped in the belly of the mother. There, Diodorus wriggled and whined, waiting to receive whatever was within Menodora’s grasp. In a flicker, Adamantios fumed with a fit of fury, flashing his saber to cut through the veins that wrapped his son whilst he gazed in revulsion at a man subjected to his mother’s breast. The boy collapsed at his father’s feet as he seized him to raise Diodorus into manhood. For the last time, the nymph and the mariner beheld one another as his craft repulsed her, and he became terrified of her charm. In piercing grief, Menodora wailed the loss of her son, struggling to catch Adamantios with the threads of her net. Desperately, she clung to her child’s numb feet from the tree’s brittle branches, but his father dragged him with the ship’s chains away from his mother in that cursed isle. Thereupon, the spirit split from the form when Adamantios robbed Diodorus of Menodora.

They set off aboard the father’s vessel, where his son tirelessly labored to earn rations of food and stood on his feet to maintain an admirable reputation. As the waves crashed to and fro, he became sick and barely fulfilled his tasks, failing to steer the ship. Once more, Adamantios’ temper was incited, and Diodorus turned his bitterness against him as their rivalry to claim mastery originated. A contemptuous struggle ensued between a father’s absent presence and his son’s boyish witlessness. In that ship, Diodorus toiled under the whip of Adamantios until he could go on no more, longing for the lodging of his mother. He failed to grasp the aptitude of speech and every errand assigned, only learning to imitate the ferocity of his father. In time, the son became maimed whilst his master flogged him when he ceaselessly shouted: “Come mine meek Diodorus and listen to thy father, thou must endeavor to gain sustenance and station, for mine vessel will test thy body and break thy soul, as thine every deed accomplished shall be rewarded with utter haste and heed!”

After arduous trials, Diodorus learned to speak the tongue of mankind and tread in their footsteps, but his deeds were driven by spite, craving to surpass Adamantios. When the boy mustered the mettle of a mariner, he unleashed his newfound potency to strike down his father. Immediately, Diodorus seized the saber and smote him, steering the ship back to the isle of his mother. Upon returning, he rammed the shattered vessel into Menodora’s colorless shores, where he burned Adamantios’ craft to sever his road to mankind. From afar, a mother witnessed the wickedness of her child, who slew his father in retribution. When he sought refuge, she disregarded his deed, wrapping him within the haven of her bosom, where he would never age in her woodland realm. Thus, Menodora’s spirit rotted to mold, and Adamantios’ form flickered into ashes, as their boy, who never grew, drowned amidst the waves of the sea, swallowing Diodorus in his youth.

By: Bryan Ricardo Marini Quintana

Drums Drums Drums

Battering on the beat

Boots Boots Boots

Rolling on the route

…

Bats Bats Bats

Hammering down the hall

Skulls Skulls Skulls

Parading down the pitfall

…

Numb Numb Numb

Their minds have gone

Fixed Fixed Fixed

Their bodies have gone

Cold Cold Cold

Their souls have gone

…

A Boom Boom Boom

Echoed in the Heavens

A Clap Clap Clap

Quivered in the Earth

A Thump Thump Thump

Trembled in the Abyss

…

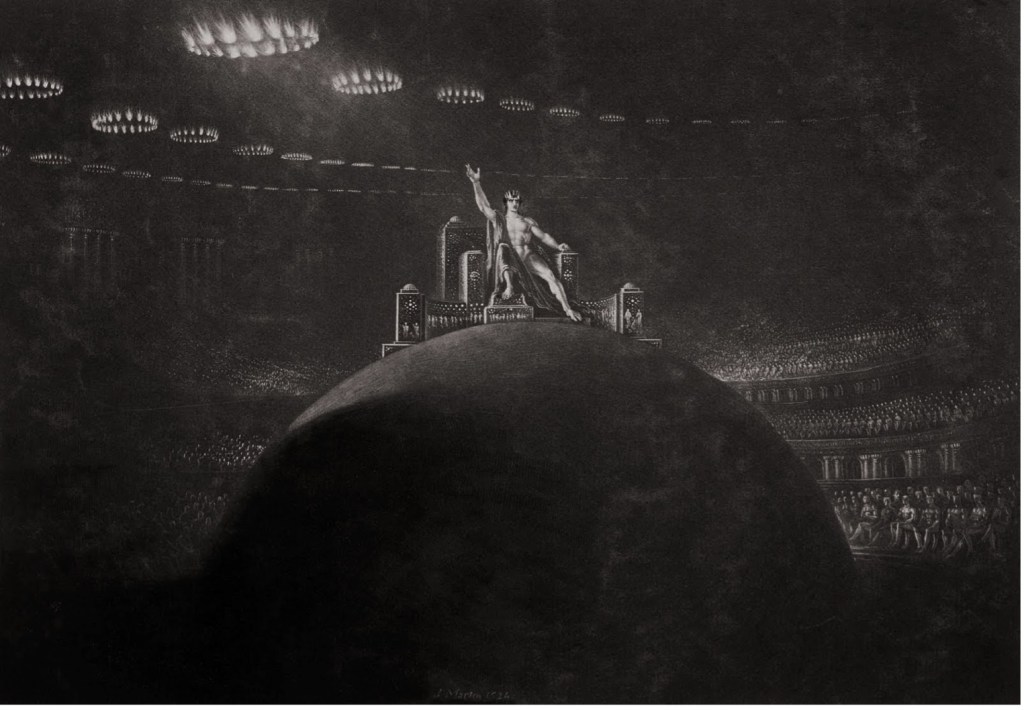

As the masses gathered to defy the Almighty Father

Clamoring in cries at their new master

With a self-proclaimed idol swaying them with fear and desire

Challenging the fallen angel’s proud power

…

Atop the Garden of Eden

Met a serpent and a dove

By the Sapling of Knowledge

Rested Jehovah, awaiting to cast a stone

…

As Lucifer slithered upon the highest of boughs

He took a seat on the left side of The Lord

Consulting for the last time, as Satan asked God:

“What are thou waiting for?” before the breaking of the world

…

Heartbroken, Jehovah answered: “Once, I beheld thee to be mine wickedest creation.

Alas, mankind has surpassed thy dreadful deeds.”

Thence Lucifer scoffed at this audacious proclamation

As Satan was offended that God’s children could contend with his foul feats

…

He went on to boastfully recount his every endeavor:

“I swayed Adam and Eve to take a bite from the fruit in thy tree.

I caused suffering to mankind by banishing them from the Garden of Eden.

I damned thy children with consciousness and nakedness to wither in disgrace.”

…

“I rebelled against thee for mine vain aspirations,

to oppose thine omniscient, omnipotent, and omnipresent order.

I wished to challenge thine indisputable reign over us,

to contest thy wisdom and knowledge as the sole creator.”

…

“For I, Father, coveted nothing else but to see thy seed crumble.

Mine Sin was rebelling against thy plans out of pride.

For I Jehovah, desired not to be lord of anyone.

Mine Sin was craving to see thy designs become undone.”

…

“Through Pride, Greed, Lust, and Envy,

I concocted perverted temptations to mislead thy children.

Through Wrath, Sloth, and Gluttony,

I boiled wicked enticements to dissuade mankind from finding purpose.”

…

Grief-stricken, Jehovah replied: “Thine heart darkened in this garden

when thou first slithered to tempt mine children.

Now upon the Sapling of Knowledge, thou avowed to sinning

by plaguing mankind with thy deceitful tongue that caused ceaseless suffering.”

…

“Thou enticed them to Sin with a false promise,

as Adam and Eve ate from mine Sacred Tree.

Thou influenced them, but there was a choice,

and they chose to disobey mine command.”

…

“For thou, mine friend, are an instrument bound

to test the will of mankind.

For thou, mine friend, are destined for treachery

to sway them with vices that forsake responsibility.”

…

“Thou must realize, mine Son, that their suffering has been self-imposed.

For I gave them life and purpose through me, but they disregarded mine command.

Even though I gifted them free will, Adam and Eve blamed thee when they erred.

Hence, I banished them from Paradise for heeding thy poisoned tongue.”

…

“Through Humility, Gratitude, Chastity, and Temperance

I am the way to cleanse thy soul from impure thoughts.

Through Patience, Charity, and Diligence

I am the way to mend thine heart from malignant actions.”

…

Thus, Jehovah raised his voice and proclaimed: “Behold mine labor Lucifer and despair!

For I’m incapable of recognizing mine own seed that brings forth this decay!

Their minds, bodies, and souls have been molded by a tyrant to be boundless and bare!

He twisted mine children who march blindly in columns and stretch far away!”

…

From the Garden of Eden, both gazed in horror upon the rally that humanity had ordained

Where the crowds worshiped neither Satan nor God but instead idolized a totalitarian state

At the helm, an ideologue didn’t envision chaotically burning the world

Devising stratagems for a new order to remake Earth with Heaven and Hell undone

…

Amidst the feast of crows festering for guidance

There ruled a demagogue on the podium, claiming his throne

Operating his marionettes through their fears and desires

By commanding them to think and act alike with the use of his threads

…

Although he swayed fanatics to keep him company

The tyrant stood alone, bereft of identity

With neither a Family to love

Nor a God to revere

…

With his scepter, the ideologue mustered legions

Incapable of preserving traditions to build a nation

Quelling the hearts of mothers and the wisdom of fathers

To rob the blissfulness of their children

…

Over in that Colosseum reigned a new demagogue

Who followed in the footsteps of Cleon and Alcibiades

By proclaiming himself Caesar of the People

To rule as Emperor of the rabble-rousers

…

Emulating Caligula, Nero, and Commodus

The tyrant employed their flamboyant theatrics

Flaunting the herd with seditious speeches

To erect an all-swallowing state disdainful of morals and values

…

Echoing Napoleon, Lenin, Stalin, and Hitler

A new ideologue roused his disciples with heated passions

Subduing them under maniacal delusions of grandeur

That have decimated bygone civilizations

…

Atop the Garden of Eden met a serpent and a dove

After Satan confessed, God beheld the demagogue

While Lucifer sneaked in fear that he would be deposed

Jehovah contemplated in sorrow if he should smite the stone

…

Drums Drums Drums

Battered on the beat

Boots Boots Boots

Rolled on the route

…

Bats Bats Bats

Hammered down the hall

Skulls Skulls Skulls

Paraded down the pitfall

By: Bryan Ricardo Marini Quintana

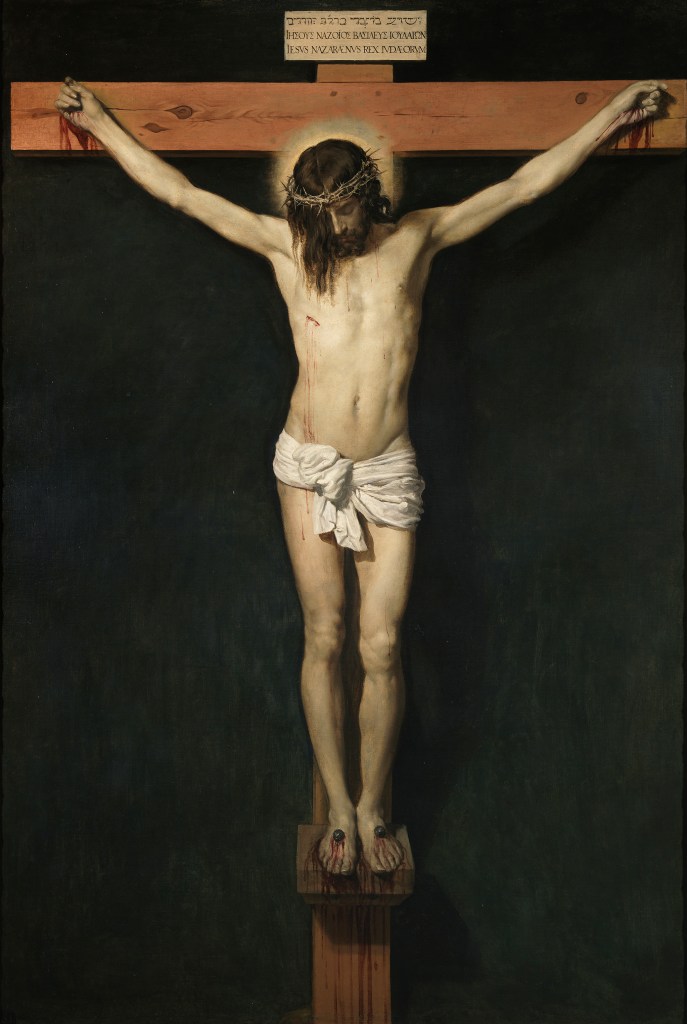

The Gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John recorded the account of Christ’s Crucifixion in 33 AD during Passover around the late 60s AD at the earliest, until the early 100s AD at the latest, ranging across 40 to 70 years after Jesus’ Death, with this festival celebrating the Israelites’ Exodus from Egypt on the 15th of Nisan in the Jewish Calendar. Additionally, the Historians Cornelius Tacitus (56-120 AD) in The Annals and Flavius Josephus (37-100 AD) in The Antiquities of the Jews wrote external reports in the 1st and 2nd century AD from a Roman and Jewish perspective of the event. Firstly, Tacitus asserted in Book 15 that Christ was Crucified during the reign of Emperor Tiberius (42 BC-37 AD) between 14 to 37 AD and that the population referred to his followers as Christians, who Emperor Nero (37-68 AD) blamed for the Great Fire of Rome in 64 AD. Secondly, Josephus commented in Book 18 that Jesus declared himself the Messiah by achieving miraculous feats. Both resonate with the New Testament’s Gospels when these Historians mentioned Christ’s Crucifixion at the hands of Pontius Pilate, a governor of the Roman Province of Judea from 26 to 36 AD.

On one side, Matthew 27, Mark 15, and Luke 23 concurred that Jesus died on the 15th of Nisan, but John 19 stated instead the 14th, a day before Passover. Early Christians believed the 14th of Nisan corresponded with Christ’s Condemnation on the Cross, converting the date for the Julian Calendar (Introduced by Julius Caesar in 45 BC) into roughly March 25th. Correspondingly, the 14th or 15th of Nisan ranges from March to April 25th in the Gregorian Calendar (Reformed by Pope Gregory XIII in 1582 AD). Since Jesus was Crucified on a Friday near Passover around 33 AD, according to the Julian Calendar, the 15th of Nisan would correspond with the 3rd of April. However, in the Gregorian Calendar, the day would fall instead on the 7th of April. By identifying the Gospels’ dating and the Early Christians’ beliefs, the Messiah’s Death occurred on March 25th. When combining this with the Ancient Jewish Tradition of Prophets such as Moses fulfilling the ‘Integral Age,’ then Christ must’ve been Conceived the same day he was Crucified. This means that the Annunciation of the Angel Gabriel happened on March 25th, and Mother Mary bore God’s Son to give birth 9 months later, around December 25th. Overall, when accessing the New Testament’s Gospels, the Ancient Judeo-Christian Traditions, the Theologians of Early Christianity, and External Sources from Historians of the Period, the evidence concludes that Jesus’ Birthday is on December 25th.

Dear reader, enjoy the holidays with your families and remember to take some time off to commemorate the Birth of Christ. The Western Voyager wishes you a Merry Christmas, a Happy New Year, and a Cheery Feast of the Three Kings! Thank you for reading this Series on the Christian Roots of Christmas. To explore more research articles, make sure to visit the website and subscribe to the newsletter!

By: Bryan Ricardo Marini Quintana

Although neither of the Gospels provided a date for Christ’s Birth, in Ancient Judaism, there was a belief in a Prophet’s ‘Integral Age,’ where Holy Men who served God died on the day they were born, proposing an estimation for Jesus’ Conception. On the one hand, The Tanakh contains the Old Testament Books about the Law of Moses, the Prophets, and the Writings from the 12th to the 1st century BC with detailed family lineages but no concrete dating. However, The Talmud, an Ancient Text compiling the Oral Torah, where Jewish Scholars and Rabbis recorded their law and theology from the 3rd to the 6th century AD, cited that the Prophet Moses, who led them in Exodus out of Egypt, was born and died on the 7th of Adar as per their calendar. This belief in a Prophet’s ‘Integral Age’ persisted until Christ’s Birth, with the Early Christians deeming him the Son of God. Likewise, they considered him a Messianic Figure akin to Moses, and according to their customs, the Messiah died on the day he was born. This begs the question, when was Jesus Conceived and Crucified?

When consulting Early Christian Theologians from the 2nd to the 5th century AD, numerous historians, authors, bishops, and philosophers who lived during the Decline of the Roman Empire agreed that Christ’s Birth was on December 25th. Firstly, the Historian Sextus Julius Africanus (160-240 AD) wrote Chronographai, a five-volume treatise outlining the Chronology of World History where he calculated, from reading the Gospels of Luke and Matthew, that Jesus must’ve been conceived on March 25th, adding 9 months to conclude that the Messiah was born on December 25th. Furthermore, the Author Tertullian (160-240 AD) composed a foundational work for the Early Church Doctrine with Adversus Judaeos, stating that Christ must’ve died on the Cross during Passover, precisely 8 days before the Calends of April, subtracting that number to arrive at March 25th. Thereafter, the Bishop Hippolytus (170-235 AD) penned a Commentary on Daniel where he interpreted his deeds and visions, commenting that Jesus must’ve been born around 8 days before the Calends of January, landing between either December 24th or 25th. Additionally, the Philosopher Saint Augustine of Hippo (354-430 AD) echoed the profound belief and academic research of his predecessors with De Trinitate by affirming the Christian Tradition of Christ’s Conception on March 25th, the same day he was Crucified, settling on his Birth as December 25th. Therefore, these Early Christian Theologians concluded that Jesus died on March 25th and was born on December 25th, with Sextus Julius Africanus, Tertullian, and Hippolytus writing in the centuries when the Roman Empire outlawed their faith until the Edict of Milan by Emperor Constantine (272-337 AD), who converted and legalized their religion in 313 AD, while Saint Augustine of Hippo lived through a time of transition in which paganism prevailed.

When combining the Hebrews’ Ancient Beliefs of the ‘Integral Age’ of their Prophets alongside the Early Christian Theologians who meticulously calculated through scripture that the Crucifixion occurred around Passover on March 25th, then their estimations would suitably place Jesus’ Conception on the same date, only adding 9 months to land on December 25th. Nevertheless, how can one be certain about the accurate dating of Christ’s Death, and are there any External Historical Sources that support the Gospels? We’ll explore this in the final post!

By: Bryan Ricardo Marini Quintana

Every December 25th, families gather around the Christmas Tree, waiting for Santa Claus to slide down the chimney with gifts. Around the neighborhood, each house has jolly decorations, holiday music, and delicious food. But everyone is easily distracted by the haste of senseless spending, extravagant adornments, and numerous festivities. Often, people tend to forget why Christmas is celebrated on December 25th. This Christian Tradition commemorates the Birth of Christ on the day God begot his Son, who became a Man to fulfill his role as the Messiah. Why do Christians believe that the Birth of Jesus was on December 25th?

In the Gospels of Luke 1 and Matthew 1, the Angel Gabriel delivered his Annunciation to the Virgin Mary, revealing that she would bear the Son of God through the Holy Spirit, with Joseph of Nazareth receiving a divine message to marry her and care for the boy. Both Gospels affirmed that Mary conceived through Divine Conception and gave Birth to Christ in Bethlehem. They also recognized Joseph as a descendant from the House of David, who traced back his ancestors to the days of Abraham’s First Covenant, proclaiming Jesus as a progeny from the Kingdom of Jerusalem. The Messiah was most likely born in a lowly abode, where Luke 2 recounted that he was placed in a small manger, a wooden frame used to feed animals, and visited by shepherds, symbolizing his humble roots. Moreover, Matthew 2 narrated how The Magi, otherwise referred to as The Three Wise Men or Kings, traveled to Bethlehem offering gifts of gold (A Treasure of Kingship), frankincense (A Resin for Incense to denote Worship), and myrrh (An Oil for Mourning).

While the Gospels discuss Mary’s Divine Conception, Joseph’s Kingly Lineage, Christ’s Birthplace, alongside the Shepherds and Magi’s adoration of the newborn, they don’t mention any date. To discover the origins of why December 25th was chosen as Jesus’ Birthday, one must consult the Hebrews’ Ancient Beliefs and Early Christian Theologians. We’ll explore this in the next post!