By: Bryan Ricardo Marini Quintana

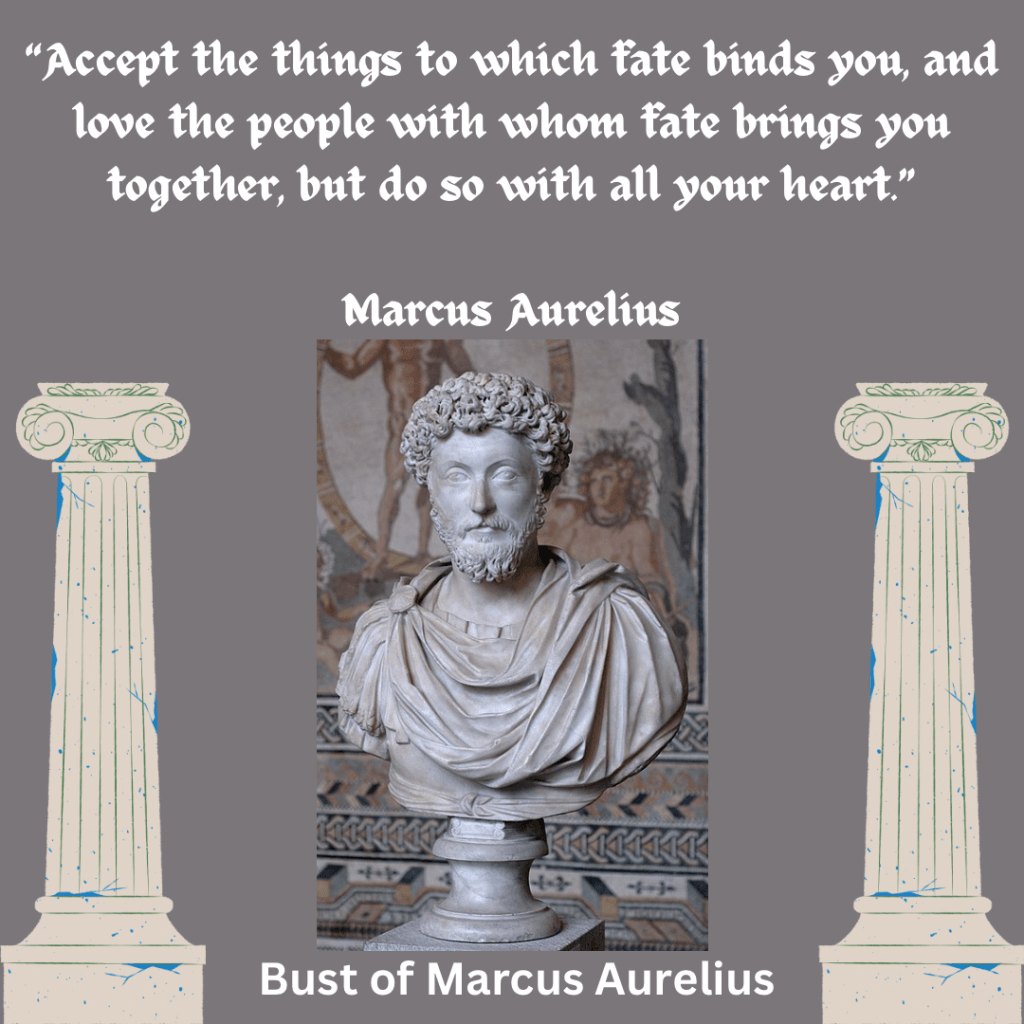

In Meditations, the Emperor reflected on how to lead a virtuous life in accordance with four chief virtues that allow a man to live in harmony with nature. These are categorized into wisdom, justice, fortitude, and moderation. Throughout the text, Marcus Aurelius explored how to deduce a man’s character based on his moral or immoral behavior by declaring: “If it is not right, do not do it: if it is not true, do not say it.” (Meditations 126) Alongside, he pondered how everyone is destined to receive his rightful due and should be prepared to face the consequences of his actions. Next, the Emperor contemplated the importance of persevering amidst the constant toiling and suffering that must be tolerated in life. Finally, Marcus Aurelius remarked on how to live in utter simplicity by employing self-discipline toward the proclivity for earthly desires.

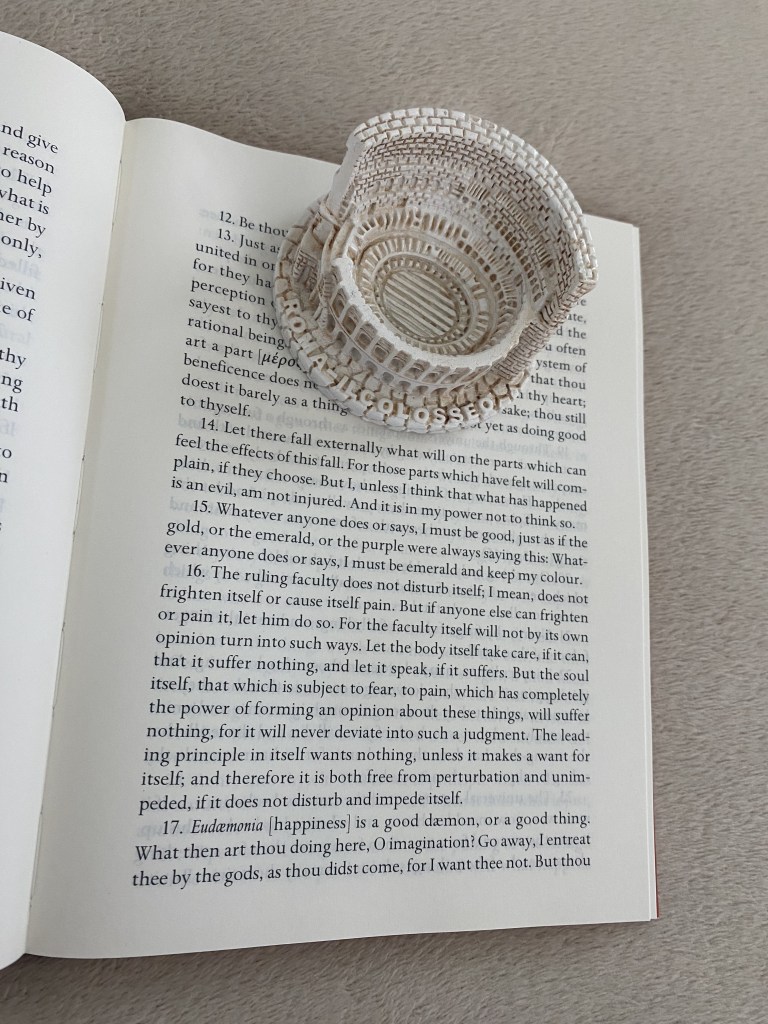

A critical teaching reverberating in Meditations is the mastery of the self, with the Emperor expressing a need to conquer his emotions. Here, he observed that one must learn to overcome his fits of passion or risk falling into an adrenaline rush of poor decision-making. From this philosophical thought, Marcus Aurelius affirmed: “Be thou erect, or be made erect.” (Meditations 63) Only by gaining control over his impulses, could he learn to live judiciously and purposely. Although Marcus Aurelius would experience pleasure, anger, grief, despair, temptation, and pain, these would not influence his reaction to outer events. By subduing his emotions, the Emperor maintained the ruling faculties that defined his character, leading to a more fulfilling human experience by finding happiness through a stable life of inner peace. Another personal reflection of Marcus Aurelius clarified this when he said: “Whatever anyone does or says, I must be good, just as if the gold, or the emerald, or the purple were saying this: Whatever anyone does or says, I must be emerald and keep my colour.” (Meditations 63)

Furthermore, the Emperor echoed the philosophy of the Pre-Socratics with Heraclitus’ teachings on the world’s nature and the principle of universal change. Firstly, he wondered why men should fear transformation when this is a natural stage of maturity between an individual and his environment. Both require alteration to uncover their true visage, meaning that for a garden to bloom in the spring, one must risk its withering in the fall. When speaking of change, Marcus Aurelius ruminated: “Is any man afraid of change? Why, what can take place without change? What then is more pleasing and more suitable to the universal nature?” (Meditations 64)

Alongside, the Emperor deduced the finite scope of human life and how insignificant it is to desire marble monuments in one’s name when none will be there to remember. He reasoned that everyone is destined to perish due to the nature of men, governed by the universal law of transformation. However, some seek to be immortalized with a vainglorious recollection of themselves, appealing to the adoring masses for their deeds to live on through them. Nevertheless, he concluded that this proud act to achieve immortality beyond death is not worth pursuing due to the far-reaching and ever-stretching sands of time that sooner or later wipe out the prideful from all memory. When examining the fate of mortals and their eventual fading from history, Marcus Aurelius expressed: “For all things soon pass away and become a mere tale, and complete oblivion soon buries them. And I say this for those who have shone in a wondrous way. For the rest, as soon as they have breathed out their breath, they are gone, and no man speaks of them. And to conclude the matter, what is even an eternal remembrance? A mere nothing.” (Meditations 31)